Being a moto-journalist since 1998 and having test ridden so many motorcycles, I am constantly being asked which is my favourite or which one will I recommend to own. And since this is the review of the new Triumph Speed 400, it is a forgone conclusion to a now rhetorical reason, right? Well, you need to read to the end to find out, just like a Coen Brothers’ movie.

What is the Triumph Speed 400?

The Speed 400 is one of two variants in Triumph’s new 400cc range, the result of their cooperation with Bajaj Auto which began many years ago. The range is seen as the entry level point into the Triumph family, and both take on the shape of the modern-classic Bonneville.

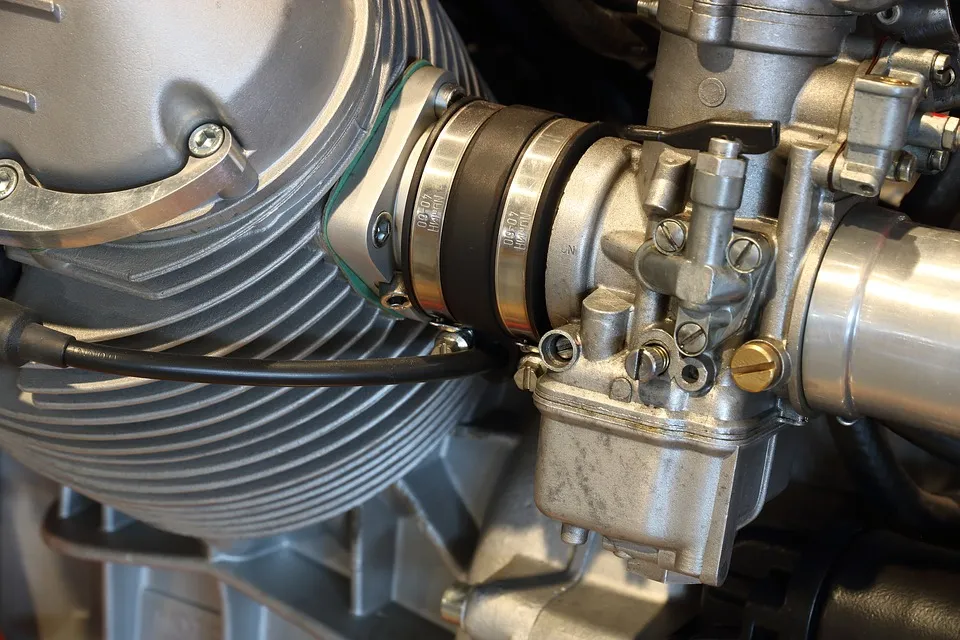

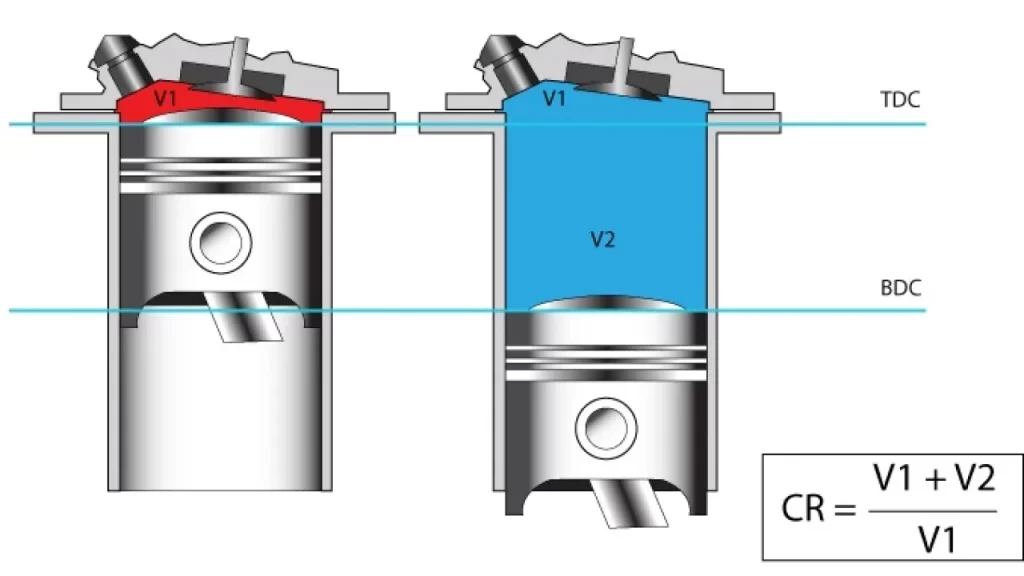

The 400 range which consists of this Speed 400 and the Scrambler 400 X are powered a 398cc, single-cylinder, DOHC, 4-valve engine which produces 39.5hp at 8,000 RPM ad 37.5Nm of torque at 6,500 RPM. Make no mistake, this is a Triumph-spec engine, unlike the one which powers the Dominar 400 which shares some of its architecture with the KTM 390 Duke’s.

Perhaps we need to reiterate that this lineup is built by Bajaj, but the bikes are definitely Triumphs.

What we liked, Number 5: The simplicity

Before motorcycles were segmented and micro-segmented into different categories, the Bonneville’s type of motorcycles were the only motorcycles, hence you can label it as a “standard motorcycle.” They were pure in the sense that there are two wheels, an engine, a fuel tank, a seat, a handlebar, footpegs.

Point is, motorcycles were uncluttered, uncomplicated, and in other words, simple. You only needed to jump on it, start, and go.

The Triumph Speed 400 embodies this perfectly. There is no need to fettle with the engine mapping, level of traction control, connect your smartphone.

Just ride.

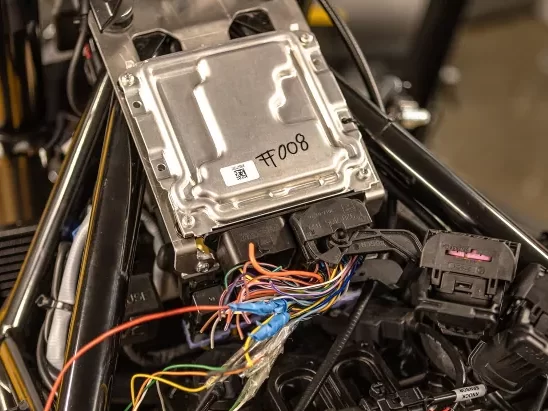

What we liked, Number 4: Its specification

While this seems like a contradiction to Number 5, it is a necessity. The Speed 400 may be an entry-level model, but it has some “hidden” modern features.

The engine is modern throughout and features EFI and liquid-cooling, and is Euro 5-compliant. Likewise, the suspension consists of upside-down forks (albeit unadjustable) and a monoshock at the back, similar to the Bajaj Dominar 400’s. The instrument panel looks classic with a large speedometer, but there is a small tachometer at the side. There is traction control which can be switched on or off, but no ride mode. Brakes are Bybre and ABS is dual-channel. There is also a USB charging port, cleverly placed behind and just underneath the instrument panel.

What we liked, Number 3: That engine

It pulled really hard. It revved so quickly that it gobbled up the first three gears instantly, causing us to run into the rev limiter the first time we hammered down. It even continued to push the bike hard in 6th from 6,000 RPM and onwards to its top speed of around 160km/h.

The good spread of torque is a character of all Triumph motorcycles, letting you accelerate hard from whichever point you currently are in the rev range, in any gear. Consequently, it made short work of riding in traffic or up our KL-Genting Highlands test route.

It needed more gear-shifting than bigger bikes when we tested it by going up the Genting Highlands road, but the torque was always present for punching out of slower corners. But because it is a smaller capacity, it never overwhelms and you are not afraid to open up, compared to bigger capacity bikes where you have to judge your throttle, braking, steering actions judiciously or risk going wide.

The throttle response was smooth – again, a trait of all Triumphs – meaning the bike reacts exactly to the twist of the wrist. And this made it so much fun hammering the bike up and down Genting Highlands.

It even cruised happily at 130km/h (8,000 RPM) all day without sounding like the engine will explode.

What we liked Number 2: Its handling!

We have said this over and over again: Triumph makes the best handling bikes and we are glad that the Speed 400 is no exception. In fact, it is the best handling Triumph!

All we needed to do was, for want of a better word, chuck the bike into any corner. See the corner, chuck it in. See another corner, chuck it in. The wide handlebar made countersteering a cinch because it responded immediately to our inputs.

The suspension may seem rudimentary but it absolutely soaked up all the bumps and holes on that road. We were a little apprehensive at first but discovered that no amount of road imperfection apart from speed bumps could throw the bike off its cornering line.

First victim to discover this was a VW Golf R32 driver who tried to race us. He was gone in just two corners. Another Proton X50 driver thought he could do the same, even by attempting to squeeze us off our cornering line. He was also despatched after two corners.

On the way down, a KTM 390 Duke rider gave chase but was left behind after the section consisting of “S” bends. Next was a group consisting of a Honda CBR250R, Yamaha YZF-R25, and several Yamaha Y16ZRs. They could not keep up after we chucked the Speed 400 through that one particularly tricky slippery and reducing radius left-hander.

On the SPE, a BMW R 1200 GS rider saw us in his mirrors and opened up. Of course, we could not keep up in a straight line due to the huge engine power deficit, yet we managed to cling on behind him in the corners as we chucked the bike around at speeds between 120-130km/h without even going off throttle. He was surprised to see us still behind when the road straightened out and he rolled out to see what bike it was.

How we wished we could paint the silhouettes of our “kills” on the side of the tank, just like how fighter pilots do!

Now, this would not have been even a blip of a talking point if the Speed 400 was a sportbike, but it is not – it is a modern classic standard. Comparing it to the likes of the 390 Duke, the Duke needs more commitment and a skilled and experienced rider to ride it fast, whereas we think almost anyone can be fast on the Speed 400. Heck, I do not think I went up and down Genting this fast even on the Triumph Street Triple 765 RS!

To put it into perspective, it was like riding a 250cc naked bike with well-sorted suspension, great throttle response, and smooth torque.

What we liked, Number 1: Accessibility and practicality

Great features, engine, handling, all wrapped up in an accessible and practical package. The seat is low and comfortable, with the handlebars placed at just the right height. The brakes were good although it needed a slightly harder pull, the clutch action was smooooooth. The gears slotted in solidly. The bike was light on paper and could be felt immediately. It went fast immediately when we wanted to be fast, and cruised serenely when we wanted to relax.

You could install a tank bag and side bags for touring. The engine is fuel efficient, wringing out 300+km from 12 litres.

And all these, for just RM26,900 (selling price) which puts it as a power player in the 250cc-400cc segment.

Shortcomings

Of course there were, but they probably due to rider preferences and riding styles.

Firstly, the first three gears where too short and the space from third to fourth a little wide. That left us changing up and down between third and fourth while in traffic. This can be fixed by swapping the stock front sprocket out to one with one tooth bigger, or dropping two teeth out back. It should make the engine run at lower revs during cruises, and help with rolling speeds into corners.

Secondly, we detected iffy fuel injected between 5,000-6,000 RPM on partial throttle in all gears. We circumvented this by either using a higher gear in lower RPMs, and lower gear above those RPMs. Still, it should not exist for a Triumph.

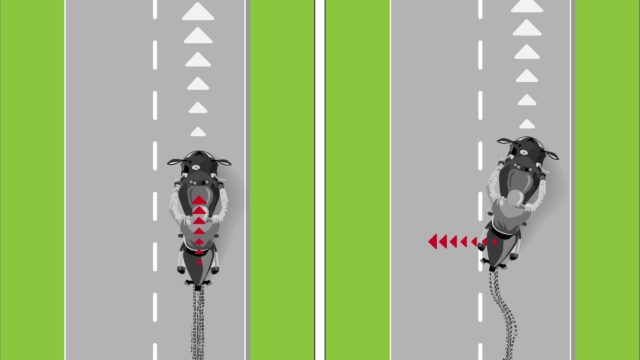

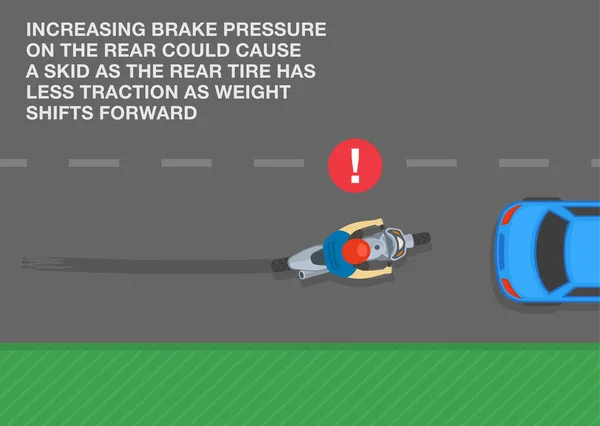

Thirdly, the bike tended to squirm during hard braking due to the aggressive steering angle (24.3 degrees). However, this was cured by clamping our inner thighs hard onto the sides of the fuel tank. That said, they bike does not like being trail braked into corners due to its rearward weight distribution, consequence of its riding position. It also waggled the handlebar in really high-speed corners. We suspect this can be easily fixed by increasing the rear shock’s preload to move more weight to the front.

However, these are just (very) minor niggles to detract from the overall enjoyment of riding the bike. We had to come up with these for the sake of a balanced review.

Closing

Coming back to the opening, can I place the Triumph Speed 400 as one of my personal favourites? And would I recommend buying it?

YES. And YES.