The Malaysian authorities have finally mandated the fitment of ABS to new motorcycles 150cc and above beginning next year. It is something many quarters including motorcyclists and transportation safety experts have requested for a long time.

However, we need to understand more about what it is and how it works, because there is no point of having the feature without knowing so. In fact, there are many fallacies about ABS that could endanger the rider’s life and limbs instead being useful.

Misconceptions about ABS

Let us start with this before explaining further.

- “ABS activates whenever I brake”

Not true. ABS only activates if the rider brakes so hard that the wheel is starting to lock up (stop moving). It is only so when the system triggers, not during every facet of braking.

- “ABS helps me stop quicker and in shorter distance.”

Not necessarily. The system does help the bike to stop quicker if one brakes super hard over a dry, grippy surface as the threshold between maximum braking power and the wheel locking up is much higher.

However, maximum braking over a slippery surface may take a little longer as the tyre is more prone to locking up/sliding i.e. hard braking over wet painted road lines. As such, the system activates earlier/easier to let the wheel continue turning, resulting in a longer stopping distance.

- “ABS prevents me from braking harder.”

Not true. ABS activates because the rider has exceeded the tyre’s available traction, thus he cannot brake harder even without ABS.

- “ABS adds too much weight.”

This was true with the older systems which weighed 11 kg in 1988. Current systems could weigh as little as 0.7 kg.

- “I can release the lever and reapply braking quickly if the tyre loses traction.”

True, but no human can match the ABS’s 24 Hz frequency, besides applying the correct amount of brake pressure.

What does ABS do?

- ABS stands for anti-lock braking system.

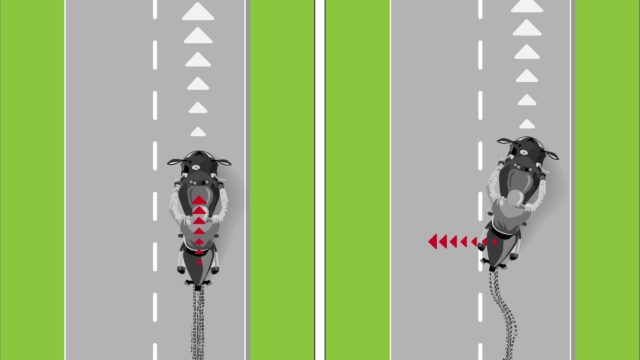

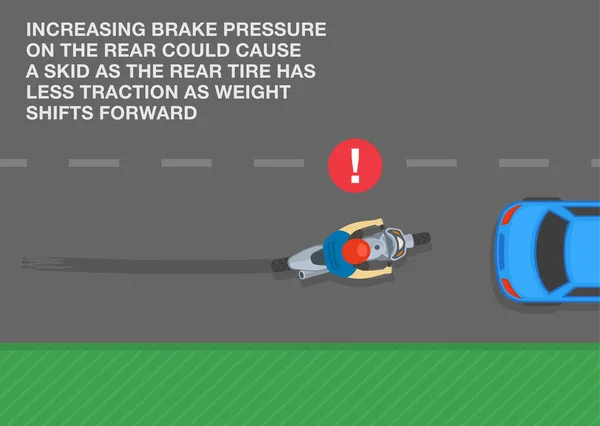

- It avoids the wheel or wheels from locking up (becoming stationary), especially when hard braking is applied whether in panic situations or over slippery surface.

- Locked wheel/wheels result in loss of control and skidding.

- Therefore, ABS assists the rider to slow down or stop while in control.

- Depending on the motorcycle’s speed, the rider can also swerve to avoid the hazard (example: a car pulling out in front of you) because the wheel(s) continue to roll.

Advantages of ABS

- Most effective braking is at the threshold of wheel lock-up. In other words, just when the tyre is about to lose traction and cause the wheel to stop moving.

- Therefore, with ABS, the rider can brake at maximum pressure without losing control.

- Prevents wheels from locking up and skidding under heavy braking.

- The rider can still steer the bike during extreme braking.

- Better control under hard braking on slippery surfaces.

How does ABS work?

- A small metallic ring gear is attached to each wheel (for dual-channel ABS).

- The ring gear is also called tone ring or tone wheel.

- A magnetic sensor is placed over the tone ring.

- The resulting electrical pulses from the sensor are sent to the ABS electronic control unit (ECU).

- The ECU is linked to the ABS pump.

- There are valves in the pump.

- The ECU measures the frequency of the pulses from the tone ring.

- If the ECU senses a dramatic and sudden drop in the pulses, it knows the wheel is about to lock up.

- When the pulse reaches zero (the wheel has stopped rotating), the ECU will close the valve in the pump to reduce the brake fluid’s hydraulic pressure.

- The drop in pressure eases the brake pads away from the brake disc.

- The wheel will rotate again due to the bike’s forward momentum.

- Brake pressure will resume immediately following the release, as long as the brake lever is pressed.

- The pressure release/re-application happens up to 24 Hz (24 times per second).

- The process will continue as long as the brake lever is held down or until the bike stops.

IMPORTANT NOTE TO RIDERS

- ABS only activates when the wheel(s) start to lock up.

- The brake lever(s) will pulsate when ABS activates.

- Do not release the lever(s) when they pulsate if you still need to continue braking.

- ABS provides the chance to steer or swerve away from the hazard (example: That cat crossing the road), so look away from the hazard to avoid target fixation and STEER!