-

We visited the Triumph Factory Visitor Experience during our trip to London.

-

The visit included a factory tour in addition to the “gallery.”

-

The center featured significant models in Triumph’s history, highlights in R&D, new models, custom bikes, and much more.

Besides witnessing the launch of the 2019 Triumph Scrambler 1200, the other main highlight was visiting the Triumph Factory Visitor Experience, during the Triumph Motorcycles Malaysia London Adventure.

To recap, this writer had won the lucky draw’s Grand Prize during the launch of the 2018 Triumphs that included the two Tiger 800 variants, Bonneville Bobber Black and Bonneville Speedmaster.

The trip coincided with Triumph Motorcycles’ Global Dealer Conference (GDC) and launch of the 2019 Bonneville Scrambler 1200. Thus, the entourage included Dato’ Razak Al-Malique Hussein, the Chief Executive Officer of Fast Bikes Sdn. Bhd. (the official distributor of Triumph motorcycles in Malaysia); his son Rafique; the Tan family of Triumph Motorcycles Bukit Mertajam and Guan How Superbike; and Asep Ahmad Iskandar, the founder of the Art of Speed Malaysia.

We assembled at the ExCel London at 5.30am before boarding the coaches to Hinckley in Leicestershire, the home of Triumph Motorcycles. It was good to get into the heated buses – the thermometer onboard showed 9oC outside.

The manufacturer’s HQ, factory and visitor centre complex is located 188 km from the exhibition centre but was a direct route via the oft-heard “M1” (Motorway 1). Traffic was heavy even during these early hours.

We were soon treated to the sights of the beautiful English countryside. Rolling hills and expansive pastureland were dotted with farmhouses in the yonder. Factories small and large sprung up intermittently.

We soon rolled up to the complex and an excited murmur went up in the bus. They were Triumph dealers from the world over. I heard Japanese, Korean, Spanish, American accented English.

We were shepherded to the 1902 Café and a staff member welcomed us. They also served light refreshments but more importantly, hot coffee. The café was named so for the year when the first Triumph appeared. Yes, Triumph was established earlier than Harley-Davidson.

At the back was the “wall of engines” which displayed Triumph’s engines through the ages.

Outside was the Avenue of Legends. Significant dates that represented milestones and names of Triumph riders were laid into the path leading up the main doors. I stood out here trying to believe that I was actually standing in front of THE Triumph Motorcycles Ltd. factory in England. The strong wind brought with it chilling temperatures but I didn’t care. I was too absorbed.

We shot a few photos with the Tan family along the Avenue of Legends after waiting for quite a while. He came back and complained that his children had disappeared into the gift shop as soon as they got off the bus. Who can blame them?

It was time to visit the facilities. The doors opened to a Street Triple RS and Bonneville Speedmaster in the foyer.

A new Speed Triple and classic Bonneville hung from the ceiling.

The Factory Tour

The exhibition area was choked up with the dealers, so I “‘scuse me, ‘scuse me” at a whole bunch of human torsos (that was all I saw at my height) and made my way into the factory. NOTE: No photography was allowed so there are a limited number of pictures from this area.

No, this wasn’t where random prank calls are handled. Crankshafts are made here. A case contained the Bonneville T120 crankshafts in different stages of machining.

There were many other areas along the way, of course, including engine assembly, motorcycle assembly and everything else in between. Unfortunately, the factory staff watched me intently as I shouldered a large DSLR. However, the Spanish-speaking dealers ahead were sneaking in shots with their smartphones. Merda!

We came up to a section where an elderly Englishman applied the striping to the wheels. The work was fast but the results were immaculate.

The inspection “booth” is where parts were picked up from the production line and inspected closely. Safe to say that inspection was carried out visually and with tools such as X-ray and ultrasound machines, among others.

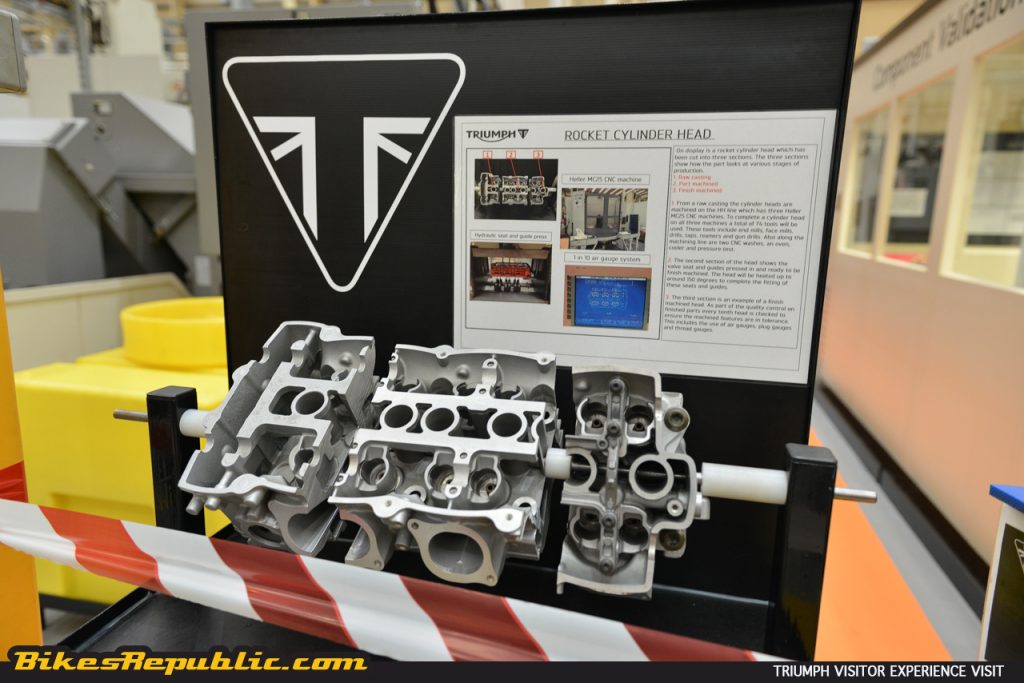

At 2294cc, the Rocket III’s engine is the world’s largest production motorcycle engine. Here are three separated pieces of the cylinder head, showing the different stages of production. On the left is the raw casting; partly machined in the centre and; fully machined on the right.

Looks like an IKEA stock area, doesn’t it? It’s the same concept here except that the bikes are fully built, instead of needing self-assembly (although I wouldn’t mind doing that!).

Triumph Factory Visitor Experience

The Triumph Visitor Experience is a gallery adjoining the main building.

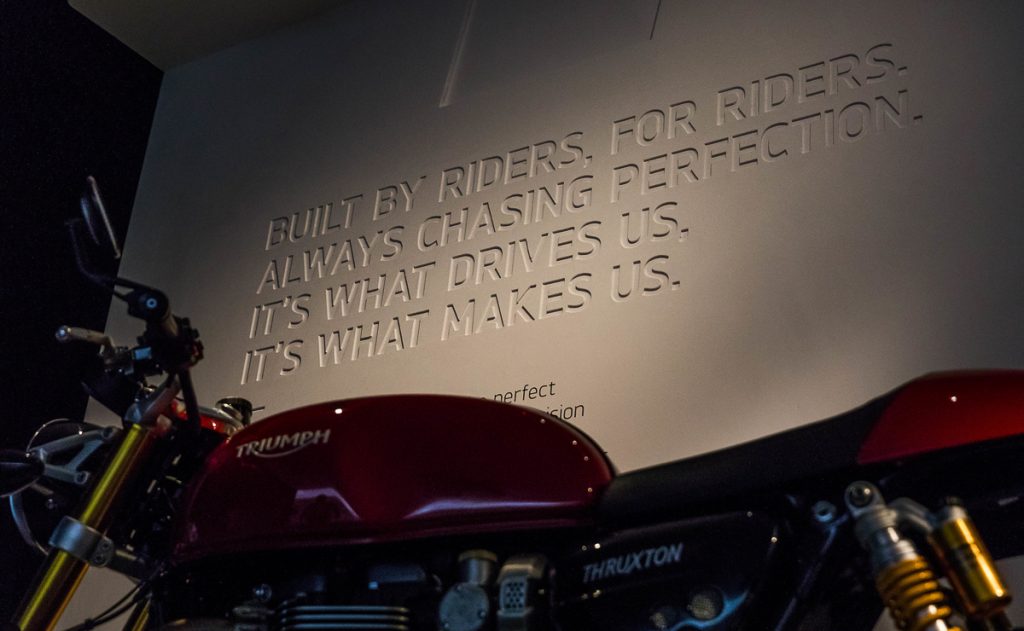

It’s divided into different segments, starting with ATTITUDE. It alludes the philosophy that Triumph was built on and what drives the brand. Etched into the wall are these words, “Built by riders, for riders, always chasing perfection, it’s what drives us, it’s what makes us.”

Although Triumph is proudly a British brand, it was started by Siegfried Bettman, who emigrated from Nuremberg, Germany. He sold bicycles originally and named his company Triumph Cycle Company in 1886, before registering it as New Triumph Co., Ltd the next year with funding from the Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company. He was joined by another Nuremberg native Moritz Schulte as a partner in the same year.

Schulte encouraged Bettman to turn the company into manufacturing. They moved to a site in Coventry in 1886 and produced the first Triumph bicycles in 1889. Now I know where my Grandad’s Triumph bicycle came from.

Anyhow, they expanded into motorcycle manufacturing and produced the first in 1902, powered by a Belgian Minerva engine. So voila, Triumph No. 1.

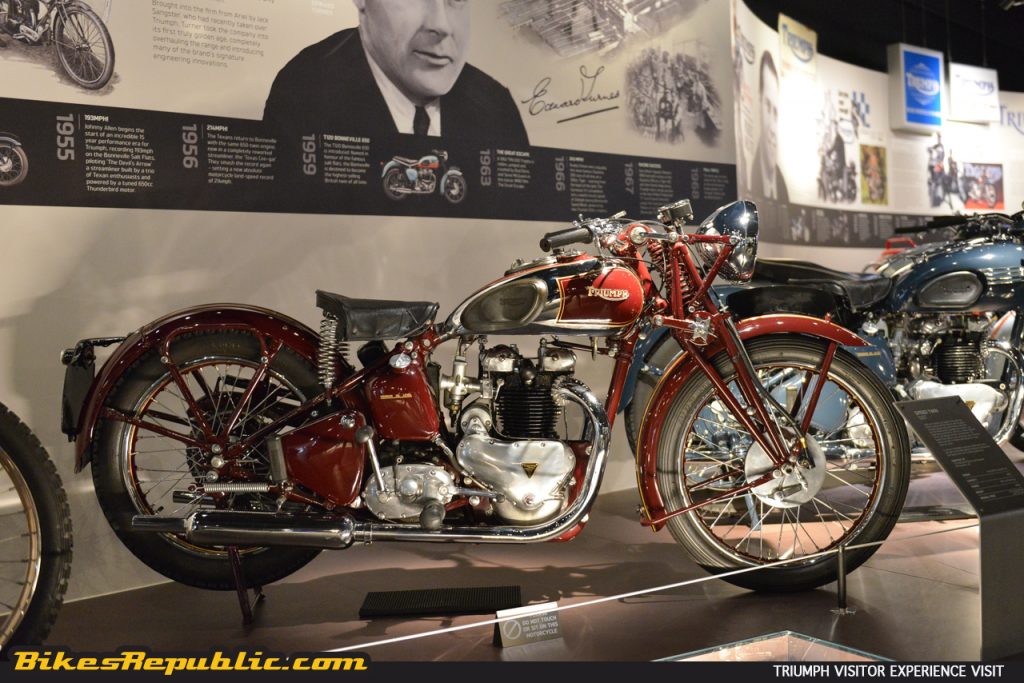

This beautiful 1937 Speed Twin had me staring at it for a good 20 minutes. Featuring a 500cc parallel-Twin, it was the first truly successful British twin and set the standards for those that followed.

Next was this X-75 Hurricane. BSA (owner of the Triumph brand back then) wanted a design that could sell in the US and employed Craig Vetter to redesign the BSA Rocket 3. But BSA went bust in 1972 so the bike was sold as a Triumph, thus the Vetter BSA Rocket 3 became the Triumph X-75. Production stopped in 1973 as the bike failed new American noise standards. I love the triple exhaust tips!

Before turning the corner, a Thruxton R sat in front of a large display case. The cubbies were filled with Triumph factory accessories. Yes, the manufacturer has more than 300 accessories to choose from.

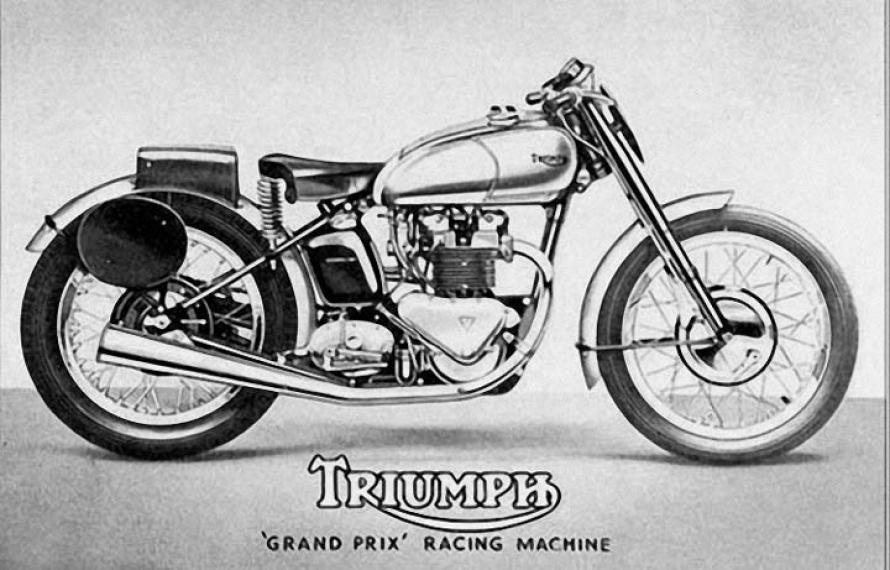

Starting the PERFORMANCE area were two race bikes. A 1947 Tiger 100 Grand Prix Mark I Racer sits in front of a 1958 Thruxton 500. The Tiger 100 was also known as the T100, so it’s the Granddaddy of the present Bonneville T100. Ernie Lyons rode the race bike to victory at Manx Grand Prix. Triumph commemorate the win by selling the stripped-down Tiger 100 race replica in 1947, which became known as the “Grand Prix.” The victory at Manx was just one of the many that the Tiger 100 won.

The name “Thruxton” actually belongs to a racetrack converted from an airfield near Andover, Hampshire. The track was well-known by 1951 and holds six-event motorcycle races as part of the Festival of Britain. Geoff Duke and John Surtees raced there. Thruxton started hosting endurance races soon after.

In 1958, the endurance race became a 500-mile (800-km) affair. Mike “The Bike” Hailwood a 650cc Triumph. This was the start of Triumph’s reputation as a fearsome competitor. Hailwood’s win was the first of eight Thruxton 500 victories for Triumph.

There weren’t exactly factory-built racing prototypes those early days. Instead, competitors buy their bikes from showrooms and modify them for racing. So, Triumph did the smart thing of producing racing parts (like modern-day race kits) and sold them to mechanics and dealers.

The first factory-built Thruxton racer was in 1964. 52 of these were made to homologate them for racing. The 1958 “Thruxton” may be the start but the supreme Thruxton was introduced in 1969. Based on the T120, it finished 1-2-3 at Thruxton, second in the Barcelona GP, and won the Isle of Man Production TT by a record average of 100 mph (160 km/h). That’s super fast for a 1969 bike!

This is why the current Thruxton model is the racer variant and alpha-bike of the Bonneville line-up. As with its descendant, it’s built on the Bonneville T120 and shares the same engine, albeit with the High Power tune.

(OMG! We still have 4 more sections to go!)

Gene Romero rode this racing 750ccTrident Triple to second place at the 1971 Daytona 200 race. It was part of Triumph Meridien’s 5-rider team assault on the pre-eminent American race. Romera finished just 2 seconds behind the winner in the 320-kilometer race (200 miles). Just below the fuel tank is the trademark “letterbox” airbox. Intake air was routed through the front of the fairing into the airbox and past the oil-cooler, like the modern ram air system. Gene Romero was a multiple AMA Grand National Champion. His teammates were Gary Nixon, Don Castro, Paul Smart and Tim Rockwood.

This Daytona TT600 won the Isle of Man TT in 2003. The bike was built by the famed Valmoto team. This was the early Daytona 600 which uses an inline-Four engine, instead of the triple in the later Daytona 675. But it cemented the Triumph Daytona’s name in the supersport category.

Ah hah. The Triumph Streamliner. Johnny Allen rode (drove?) this machine to the fastest land speed record of 214.40 mph (345.0 km/h) on 1stSeptember 1956 at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA. 345 km/h seems mild now, but this was 63 years ago.

But what made the feat even more remarkable was the engine which powered the streamliner. It wasn’t supercharged, turbocharged; not a factory-built one-off special. Only one engine normally-aspirated engine was used, instead of the twin-engine powered sleds used for breaking records. Not only that, the donor engine was a 650cc parallel-Twin which powered the Triumph Thunderbird. It was fettled a little by having larger valves, larger Amal carbs and ran on an 80% methanol/20% nitromethane fuel. But the cylinders were stock!

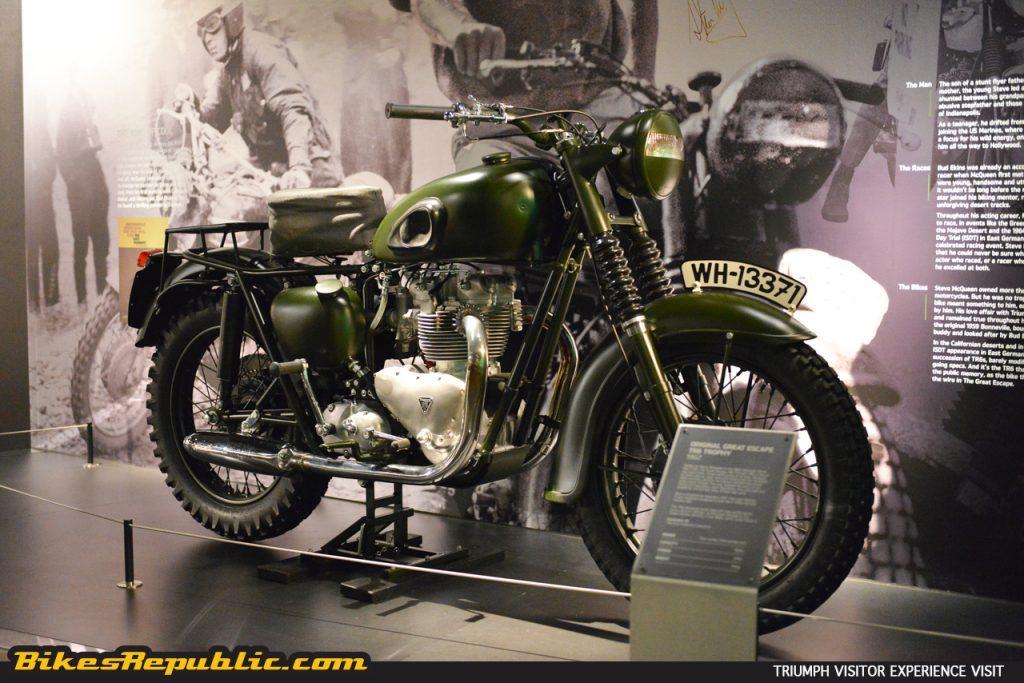

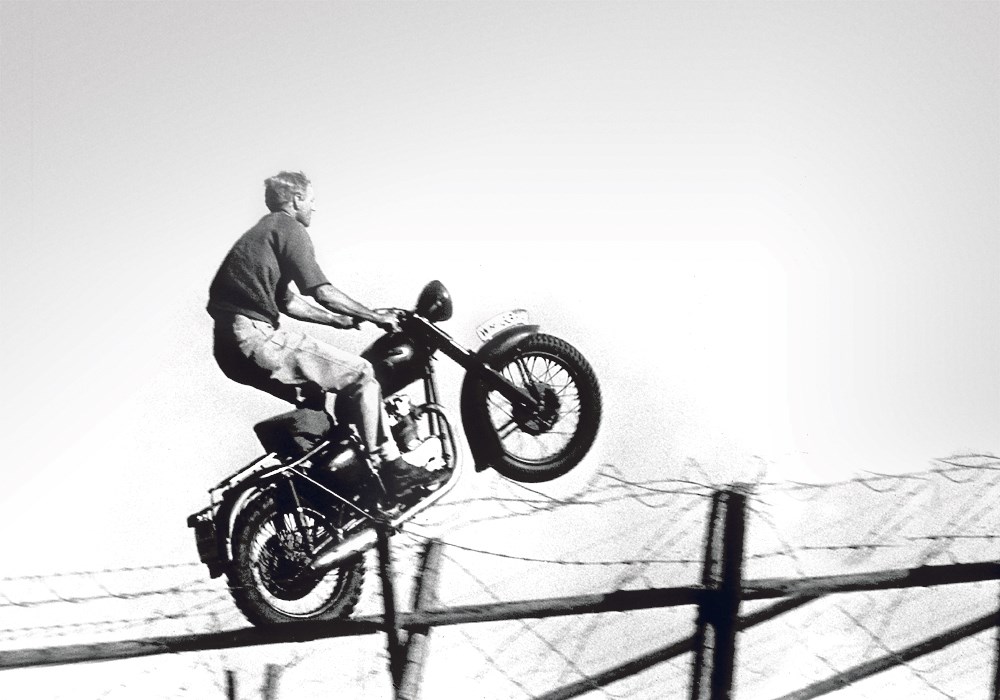

Oh yes! We’ve come to the bike I really wanted to see! It’s the original TR6 Trophy which was dressed up to like a Nazi’s R75 in Steve McQueen’s movie, “The Great Escape.” This was the legendary bike on which McQueen’s character jumped the concentration camp’s wire fences on this bike, although the stunts were performed by his stunt double and racing buddy, Bud Ekins.

The pair didn’t only use the TR6 Trophy model for the movie. They actually raced the bike in rallies, including the punishing Baja Rally.

The TR6 Trophy is the predecessor of the current 900cc Bonneville Street Scrambler and the new Bonneville Scrambler 1200.

Next to the Great Escape bike is another segment which showcases how Triumph carries out R&D and building their bikes.

The first display showed a raw aluminium ingot before it is turned into an engine casing.

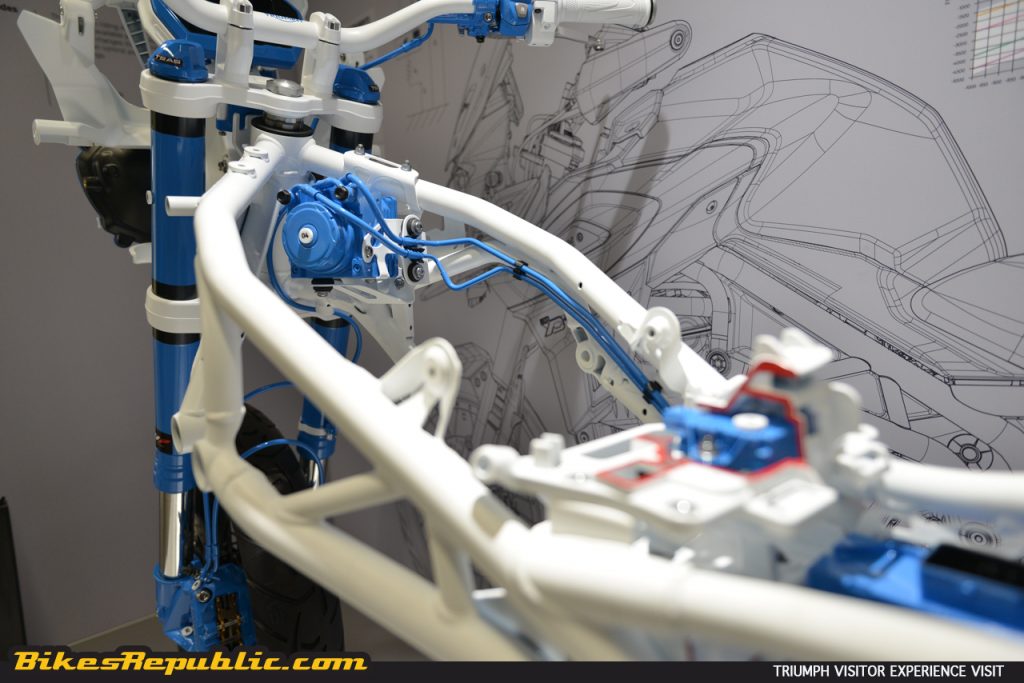

Next was the frame and chassis of a new Tiger 1200. This area showcases the R&D carried out particularly for traction control, ABS and electronic suspension.

Moving on is the section showing how Triumph designs their bikes, in particular the Bonneville Bobber. The exhibit described the stages of development from pre-concept to the clay mock up displayed here. The Bobber is Triumph’s best-selling model of all time.

Roadgoing prototypes were built for real-world testing. These are the stages we see usually see in spyshots. Although it already resembles the production bike, look closer and you’ll see a different instrument display, extra wire looms, a not-so-subtle exhaust O2 sensor, and the unmissable bracket for the GIVI box. Notice the fat wire looms that lead into it. The box carries data acquisition devices (recorders) for various performance parameters.

In the farthest corner was a wall which displayed the components of a Speed Triple like a Lego set. Visitors i.e. me, were free to inspect the intricacy and quality of each piece.

In the centre of both areas was a neon-lit island which highlighted customized Triumphs. A custom Street Twin was joined by a Bobber and were surrounded by beautifully custom-painted fuel tanks.

Opposite the island was the “Wall of Dealers.” Hundreds of displays presented Triumph’s worldwide dealer network. Triumph Motorcycles Ltd. has definitely grown by leaps and bounds since John Bloor acquired the brand in 1983.

Also, near this centre area was an engine placed in a transparent case. The inscription on a plaque said, “ENGINE 000001. THE FIRST EVER HINCKLEY PRODUCTION LINE ENGINE. 1200cc Four-Cylinder Trophy Engine. Built 1990.”

On the way out, I stopped by at a Thruxton R which wore a white and blue bodywork akin to Gene Romero’s Trident Triple racer. It was on closer inspection that I found out it was supercharged!

Just as fascinating was its background. The bike was built by British rider and four-time World Superbike Champion Carl Fogarty to race at the 2016 Glemseck 101 event. Supercharging pumped maximum power up to 148 PS and torque to a huge 157 Nm. Glemseck is the annual café racer event held in Leonburg, Germany, consisting of a bike show and 1/8-mile drag race. Fogarty owned everyone on this bike by winning all 12 drag races he entered and walked away with the overall win in the Essenza class.

On the left side of the isle is the riding gear section. Triumph is not only hard at work in developing new bikes but also technology and design of riding gear.

Further up the line were rows of the latest models, including the Tiger 1200, Tiger 800 XRT, Street Triple RS, Speed Triple, Bonneville Thruxton R, Bonneville Street Twin.

It was time to visit the gift shop upstairs.

It was packed to the gills! People were grabbing stuff off the racks, tables, benches… the cashier had beads of sweat on his forehead, while two lady staff members ran around looking for clothing items the dealers asked for. I only managed to grab a cash box which looks like an oil can, an aluminium lunchbox, a couple of teddy bear keychains and a leather card holder. The queue extended from the cashier to outside the door.

The American couple of me had loads of t-shirts and leather jackets under their arms, that the half-dumped on the cashier’s desk in a heap. It took a long time for the hapless clerk to scan through all the items and the Japanese man behind me started to sigh (you know it’s taking too long when a Japanese sighs). “That’ll be £560 pounds please.” The cheerful demeanor of the couple turned to almost-horror. Compared to theirs, my stash cost “only” £50.

Back downstairs, Asep was waiting for me outside while puffing away on a cigarette. Later, we re-boarded the bus to take us back to London.

CONCLUSION

It’s only apt that Triumph calls the centre an “experience.” While there weren’t as many bikes in the gallery as we expected, those there were of great significance motorcycling history and culture, besides to the brand. I for one still could not believe that I actually saw The Great Escape’s TR6 Trophy in front of my very eyes.

The factory visit was just as awesome. It’s almost a spiritual experience to actually step foot inside the very facility which produced my favourite bikes. At the same time, the sense of amazement never ceased as I traced the progression of a piece of aluminium ingot into a complete engine assembly, which in turn became part of a Triumph motorcycle.

Again, we would like to thank Fast Bikes Sdn. Bhd. and Dato’ Razak Al-Malique Hussein for the opportunity of a lifetime.