TEN WORST MISTAKES IN THE MOTORCYCLING INDUSTRY

We brought you Part 1 (click here) of our collection of the biggest mistakes in the motorcycle industry previously. These bungles went on to cost entire companies and claim the livelihoods of employees, but mistakes are also the catalysts for improvements. Here’s Part 2.

6. HELL-MET

Anyone remembers Skully helmets? Hopefully none of you reading this got burned.

Skully’s helmet featured a rear-facing camera, built-in Bluetooth connectivity, and a heads-up display.

Invented by CEO Marcus Weller, Skully started taking preorders in 2014 through Indiegogo crowd funding, raising US$1.1 million in record time. However, insider accounts revealed that only 20 to 100 units have been shipped as of July 12, 2016, due to production delays.

It was during the same date that Weller was removed as CEO and replaced by Martin Fischer. Despite having already raised a total of $2.5 million through the Indiegogo crowd funding program and another $11 million in venture capital from Intel and others, Weller had failed in his attempts to obtain further capital at the time.

Then, former executive assistant Isabelle Faithhaur sued Skully founders Marcus and Mitch Weller, for misappropriating company funds for vacations, sports cars and a strip club, then claiming those as company expenses. Getting wind of the lawsuit, Skully shut its doors and filed for bankruptcy.

It didn’t end there. Electronics manufacturer and Skully supplier, Flextronics had also sued Skully for reimbursements. Flextronics says Skully owes $505,703 in past-due bills, $514,409 in unpaid billes and another $1.5 million for what they spent on materials and inventory related to the Skully helmet.

Skully left behind a gawd-awful mess in its wake. More than 3,000 customers who preordered the helmets may never receive theirs, and at least 50 employees out of a job.

7. CAMS BY CADBURY(?)

The American Motorcycle Association had decreed that four-cylinder 1000cc superbikes to be downsized to 750cc beginning for the 1983 superbike racing season and that the motorcycles must be production based. (These regulations became the core of the World Superbike Championship which started in 1988.)

Being “production based” means road-legal versions must be homologated – in other words, made for the public – in contrast to the fully-prototype machines that race in the world GP championships.

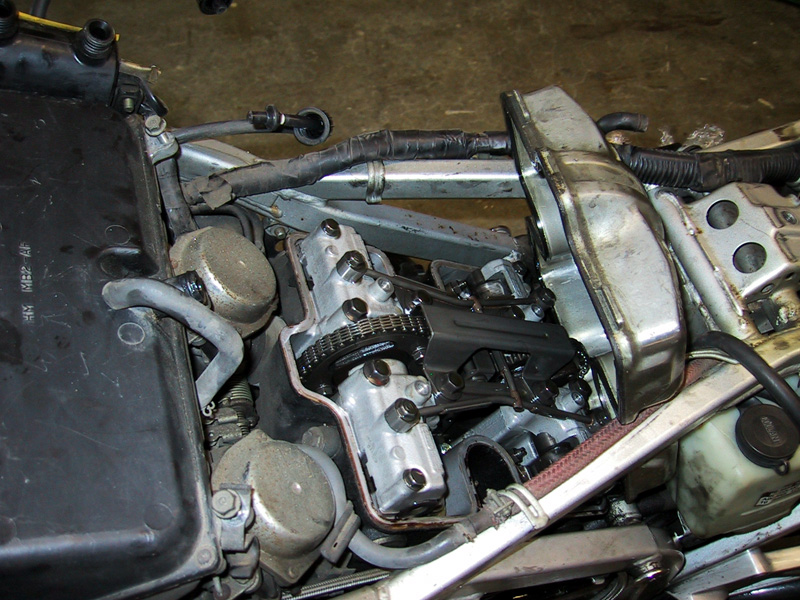

These regulations created the very first Japanese superbike repli-racer, the Honda Interceptor VF750F. Honda had wanted to win the AMA Superbike Championship and threw everything into the Interceptor make it (almost) race ready. It was the company’s founder Soichiro Honda who uttered the famous quote, “Racing improves the breed,” after all.

Consequently, the Interceptor boasted features that were once the domain of race bikes.

The 748cc, liquid-cooled, DOHC, V-Four engine produced an impressive (for the time) 86 bhp, 62.8 Nm of torque and propelled the bike to a top speed of 222 km/h, courtesy of a new airbox which forced air into the cylinder heads. Two radiators kept things cool. It was reported that the race engines produced a whopping 132 bhp.

The world’s press was impressed by the Interceptor’s handling too, as it was suspended by Showa suspension on both ends, with the 39mm front forks featuring Honda’s TRAC (Torque Reative Anti-Dive Control) system which limited fork dive, resulting in a more stable ride. Honda’s Pro-Link single shock suspended the sand cast swingarm. A rectangular steel perimeter frame was used. A section could be unbolted should engine removal was required

And while the slipper clutch is now available on virtually all modern superbikes, it made its street bike debut in the Interceptor.

Apart from the engine and chassis, Honda also worked on aerodynamics and the final styling became the shape of future sportbikes (well, at least until Suzuki unveiled the GSX-R750 “Slingshot” in 1988).

The new fairing was designed to push airflow over the top of the rider’s helmet, the lower cowl provided downforce and the fuel tank had cutouts for the rider to tuck his knees in. Honda also offered a rear seat cowl to make the bike look like its track cousin.

It looked like Honda had created the Godzilla of superbikes. The Interceptor was a sales success. But we’re talking about screw-ups, aren’t we?

Customers started to complain about erratic engine behavior and rattling, which was traced to problems in the valvetrain, or more specifically abnormal camshaft wear. Honda didn’t want to admit to the problem initially, but they concluded that it was likely due to oil starvation, besides possible valve clearance issues. Honda issued a recall and drilled holes into the cam lobes apart from closing off the cams’ ends. They also fitted kink-free oil lines and banjo bolts.

Didn’t work.

Afterwards, Honda first assumed the problem was caused by heat, only to discover there was too much clearance in the camshaft bearings. Honda responded by replacing the camshafts with a new type.

But it’s apparent that Honda had bungled on the cam lobes that were too soft, causing them to pit and wobble in the bearings. Dissatisfied customers started calling them “Chocolate Cams,” and the pejorative stuck for every motorcycle with cam problems ever since.

The Interceptor VF750F was discontinued after 1986. It had almost singlehandedly destroyed Honda’s image of quality and engineering.

Which is a shame, because the Interceptor is still one good-looking bike, 34 years on.

8. STRIKE!

I like bowling. It’s satisfying to throw 12kgs of spherical rocks down a lane and watch the hapless bottle-shaped wooden pieces scatter. There are many companies who produce bowling alley equipment these days, but one name always gets my attention.

AMF – acronym for American Machine Foundry. Although its name contains the word “machine” and “foundry” it was a sporting equipment giant.

Harley-Davidson was in dire straits in the late-60’s due to the competition of foreign motorcycles, especially from Japan in the form of a little upstart called Honda.

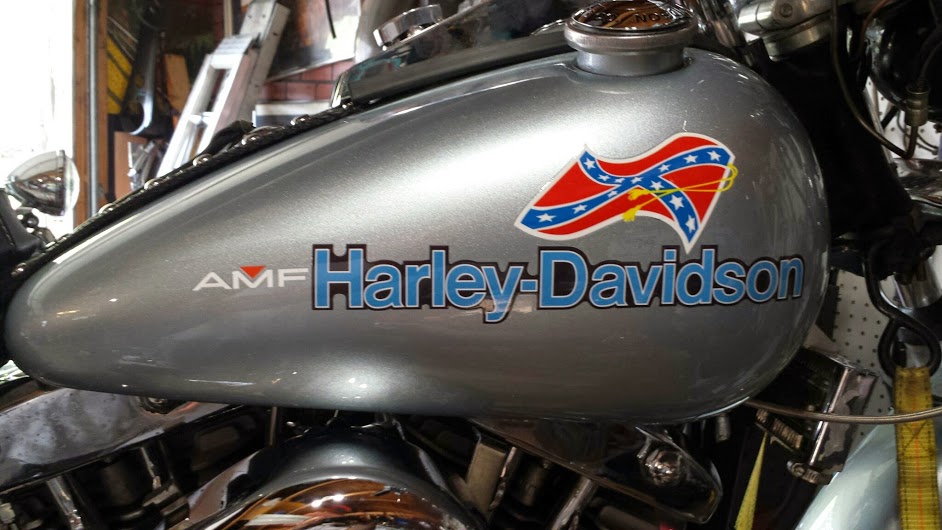

AMF threw H-D a lifeline by acquiring the Motor Company in 1969. It would’ve meant taking back H-D’s lost ground and credibility, only for it to go further south.

AMF restructured H-D by laying off a great number of employees, leading to strikes (as in labor strikes). As a consequence, workmanship and quality started to suffer. AMF operated under the “make more, sell more” principle, instead of producing motorcycles to compete in terms of price, performance and quality.

Bizarrely, Harley-Davidson even produced snowmobiles from 1971 to 1975. Then in 1976 Harley produced the “Confederate Edition” series of bikes to commemorate the United States of America’s bicentennial. These bikes had Confederate flag painted on them, sparking civil rights complaints.

A quality continued to suffer, new bikes from the factory leaked oil onto the dealers’ showroom floors. There were rumors of dealers having to using sanitary napkins on the crankcases to soak up the oil.

It was at this time that Harley-Davidson earned mockery such as, “Hardly-Ableson,” “Hardly Driveable,” and “Hogly Ferguson.” The word “hog” became a pejorative ever since.

A group of 13 investors, led by Willie G. Davidson and Vaughn Beals bought back the now-struggling company for $80 million in 1981.

Well, at least AMF kept the Harley-Davidson name from tanking in 1969 and produced models whose styling became the Motor Company’s hallmarks. And thankfully, they didn’t sound like a bowling ball rumbling down the lane.

9. RED PAINT BY DuPONT

The USA entered World War I on April 6th, 1917, joining its allies Britain, France and Russia against Germany.

It was during this time that the Indian Motorcycle Manufacturing Company sold the bulk of its Powerplus line to the US military, resulting in a dearth of availability to customers. Their dealers weren’t happy and turned their backs on Indian, as a result. Consequently, Indian lost its number one position to Harley-Davidson, by the 1920s after the war.

As business suffered further, Indian merged with DuPont Motors in 1930. DuPont’s founder, E. Paul DuPont ceased production on all DuPont automobiles and concentrated all resources on Indian. DuPont was also a giant in the paint industry and there were 24 color options in 1934.

With DuPont’s backing, Indian had sold as many bikes as Harley-Davidson by 1940. One little known fact: Indian also made other products such as aircraft engines, bicycles, boat engines and air-conditioners during this time.

When World War II started, Indian Chiefs, Scouts and Scout Juniors were used in small numbers for different roles in the United States Army, while the British and Commonwealth militaries used them extensively under Lend Lease programs. Despite being so, the Indian models could not compete against Harley-Davidson’s WLA model in the US military.

An earlier design was based on the 750cc Scout 640 was often compared to the WLA. It was deemed both too expensive and heavy. Indian later offered the 500cc 741B but was could not secure the US Military contract. Indian even made a 1200cc 344 Chief.

However, the US Army did request for an experimental motorcycle for desert warfare and Indian responded with the 841, which mounted its V-Twin engine across the frame like Moto Guzzi. Some 1,056 units were built.

Harley also joined the fray with their model XA, but both bikes were outshone by the Jeep for the intended roles and missions

Without a military contract and lack of domestic demand, Indian found itself in trouble again.

In 1945, a group headed by Ralph B. Rogers bought a controlling stake in the company, and DuPont turned over its Indian operations to Rogers in November 1945.

Rogers went on to discontinue production of the all-important Scout and began manufacturing lightweight models such as the 149 Arrow and Super Scout 249 in 1949, and the 250 Warrior in 1950; while their arch-rival Harley-Davidson stayed the course of producing heavyweight motorcycles.

The new models found little support and Indian Motorcycles wrapped up in 1953.

There was one positive contribution during Rogers ownership however. The Indian chief head fender light called the “war bonnet” was introduced in 1947. The war bonnet is mounted on every modern Indian motorcycle under Polaris.

10. BSA

Who was the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer from the mid-30’s to the early 60’s?

BSA – an acronym for Birmingham Small Arms. In fact, BSA was one of the world’s business juggernauts at its peak.

At the end of the 50’s, BSA Motorcycle ruled the world. The Gold Star dominated the tracks and showroom sales, while the A7 and A10 sold well, too. BSA owned Triumph, Ariel, Sunbeam and New Hudson. However, the motorcycle division was only a small portion of the empire, as BSA also produced cars, busses, steel, heavy construction equipment, agriculture and industrial powerplants, machine tools, weapons, ammunition, military equipment, bicycles.

In World War II, the company produced Lee-Enfield rifles, Thompson submachine guns, .303 RAF Browning aircraft machine guns (fitted to Spitfires, among others), Oerlikon 20mm anti-aircraft cannons, Sten submachine guns, Boys anti-tank rifles, and many more.

BSA was flush with cash. Which was probably why it drove BSA’s Managing Director during the 1950s, Sir Bernard Docker and Lady Docker to complacency and hedonism, instead of re-investing in new technologies and tooling.

The pair lavished vast amounts of BSA’s profits on gold-plated Daimlers complete with mink, zebra and leopard skin upholstery, and luxury yachts. He was removed in 1956 and the pair went on to live as tax exiles in Jersey.

Seeing the success of the A7 and A10 vertical twins, BSA decided on a complete redesign of the engine into the new unit construction mold, just like what Triumph had done with 500 twin in 1959. The redesign resulted in the all-new A50 and A65.

No one cared. They were ugly, vibrated hard hence didn’t sell well.

But instead of improving matters, BSA inexplicitly stopped producing the Gold Star 1963, their best-seller.

By 1965, competition from Japanese manufacturers such as Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki, besides Jawa/CZ, Bultaco and Husqvarna from Europe were starting to eat into BSA’s market share. BSA and Triumph’s models were suddenly out-of-touch. It’s apparent that BSA needed to invest in new technologies and tooling, but poor marketing decisions and expensive projects that led nowhere muddied things even further.

1968 saw BSA announcing big changes to its singles, twins and triple called “Rocket Three” for the 1969 model year. However, despite featuring more accessories and different A65 models for the domestic and export markets, they had little impact on sales. It was also the year when BSA debuted the 175cc, 4-stroke, D14/4 Bantam, blindingly believing that it could compete with the Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki two-strokes.

Motorcycle production was moved to Triumph’s site at Meridien in 1971, while engines and components were produced at Small Heath. There were many redundancies by now and BSA was forced to sell their assets. Only four models were offered: Gold Star 500, 650 Thunderbolt/Lightning and Rocket Three.

With bankruptcy looming, BSA merged its motorcycle businesses with the Bronze Manganese subsidiary, Norton-Villiers to become NVT, in 1972.

New head, Dennis Poore, had intended to produce Norton and Triumph motorcycles in England and overseas but his restructuring caused redundancies in two-thirds of the workforce and proposed to close the Meridien plant. Angered by the decision, Triumph workers at Meridien held the plant hostage for one-and-half years before brokering a deal to buy Triumph Motorcycles as the employee-owned Meridien Co-Operative. But it was too late to save Triumph and it struggled along until 1983, ultimately sold to a new Triumph Motorcycles Ltd. company based in Hinckley, Leicestershire.

Poore was left with neither BSA or Triumph as a consequence. The only NVT model was the Norton Commando. It indeed became a legend but all NVT could do was enlarging the capacity from the original 500cc, to 650cc, then 750cc and finally 850cc. The engine became over-stressed and vibrated like crazy. There’s no hiding from the fact that the Commando was an old design, being a pushrod operated parallel-twin.

As with the merger, Manganese Bronze had received Carbodies in exchange for NVT, and the plan called for the elimination of a few brands, large labor redundancies and consolidation of production at two sites. It failed due to worker resistance.

NVT was liquidated in 1978.