JOHN BRITTEN AND THE V-1000

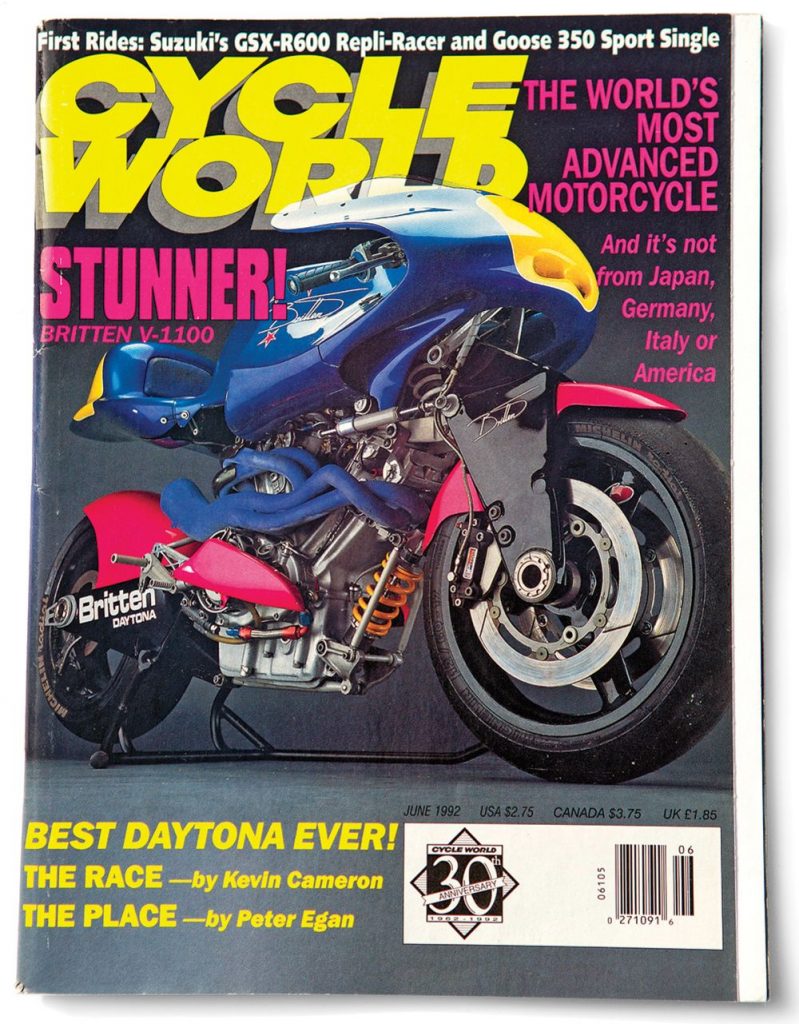

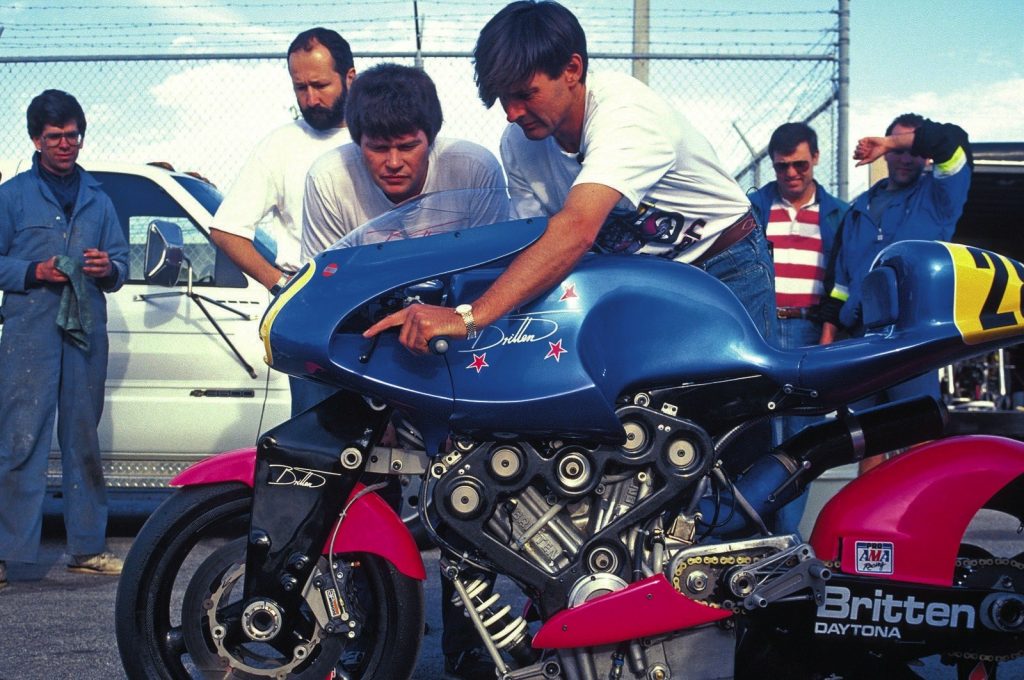

I could still remember my exact feelings when I picked up the June 1992 issue of Cycle World Magazine from a kiosk in Lot 10. On the cover was a so radical that it looked like a hippie Xenomorph (the alien in the Alien movie franchise) in blue and pink. Or at least this would be the Xeno Queen’s ride if she’s into motorcycles.

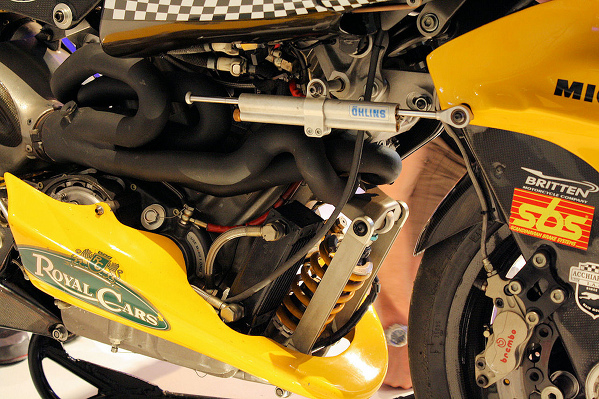

But look at those front “forks”! Those exhaust pipes! That big yellow Öhlins shock absorber hanging in front of the engine!

The copy on the magazine’s cover shouted, “THE WORLD’S MOST ADVANCED MOTORCYCLE”.

I promptly paid for the mag and hurried to the Delifrance café to read more about this “Britten V-1100.”

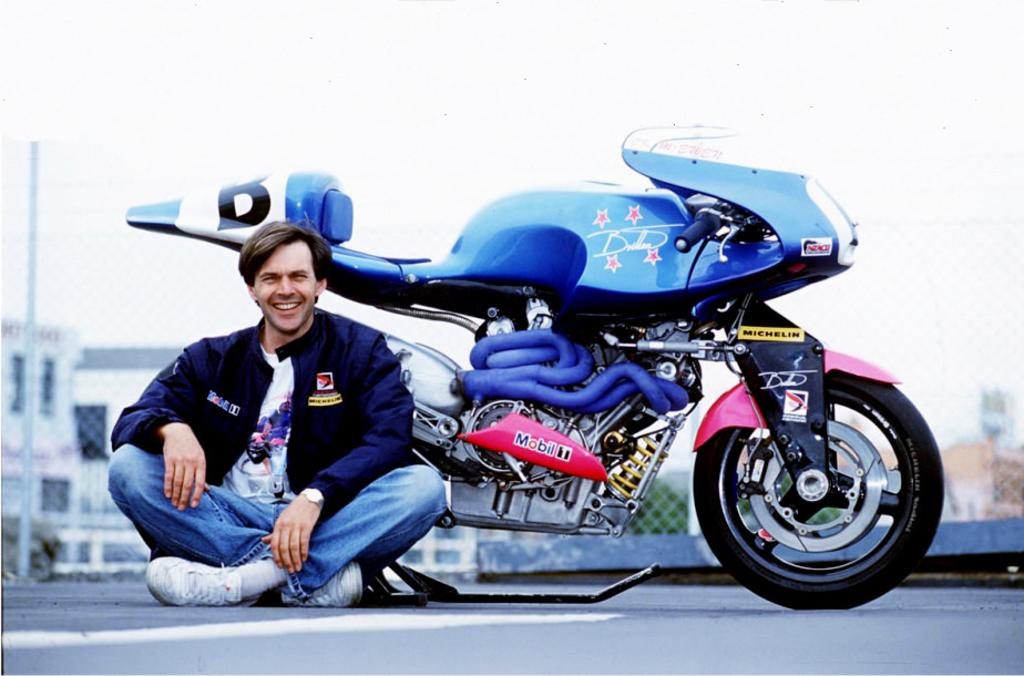

It was then that I discovered that was actually homebuilt. Yes, built in a certain genius’ backyard!

That guy’s name was John Britten.

John Britten didn’t hail from Italy, Germany or Japan, instead, he was a humble guy born in 1950, in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Britten studied mechanical engineering at a night school. This wasn’t mentioned in the mag, but I only found out while researching for this article. John Britten suffered from dyslexia.

He went to work with ICI as a cadet draughtsman afterwards. It was here that he learned to design moulds, patterns, metal spinning and other engineering designs.

Britten then embarked on a short stint in England, where he worked with a renowned civil engineering firm to build links to the M1 and M4 motorways.

When he returned to New Zealand, he became the design engineer for Rowe Engineering’s offroad equipment. He also built glass kilns and went into business as a fine artist designing and making glass lighting by hand, before joining the family property management and development business.

But John Britten had a love for motorcycles.

He was an amateur racer in New Zealand. He wanted to make something more out of his classic bevel-drive Ducati, but the engine was unreliable and the chassis didn’t handle the way he liked. He turned to a Denco engine from New Zealand, but that too proved to be unfeasible. Furthermore, ordering parts from the outside world meant they would take too long to find their way to New Zealand at the time. (It was before the internet an eBay.)

In search of the perfect race bike, Britten thus decided to build an entire bike himself.

That bike soon came to be known the world over as the Britten V1000.

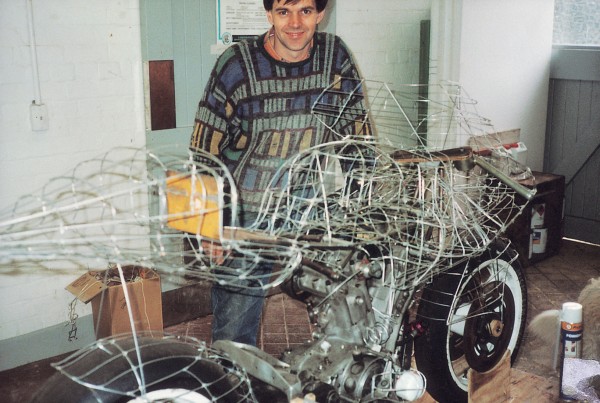

But Britten didn’t have sophisticated CAD/CAM and CNC machines, windtunnels and, an army of engineers like the major manufacturers did. All he did have was his home’s garage and a few good friends.

So how do you form the outline of a motorcycle then? Britten did it by cutting lengths of gardening wire and stuck them together with a glue gun. A clay model was then built around this frame which became the mould of the carbon fibre bodywork and other components.

The front wishbone “forks,” swingarm, bodywork and even wheels were made of carbon fibre!

Speaking of carbon fibre, Britten didn’t draw up the parts and had them made by specialist makers. Nope uh-uh, he and his mates painstakingly laid the carbon fibre material and moulded the parts themselves at home. And since this was during the late-80’s and early-90’s – the black stuff was used extensively only in Formula 1 at the time.

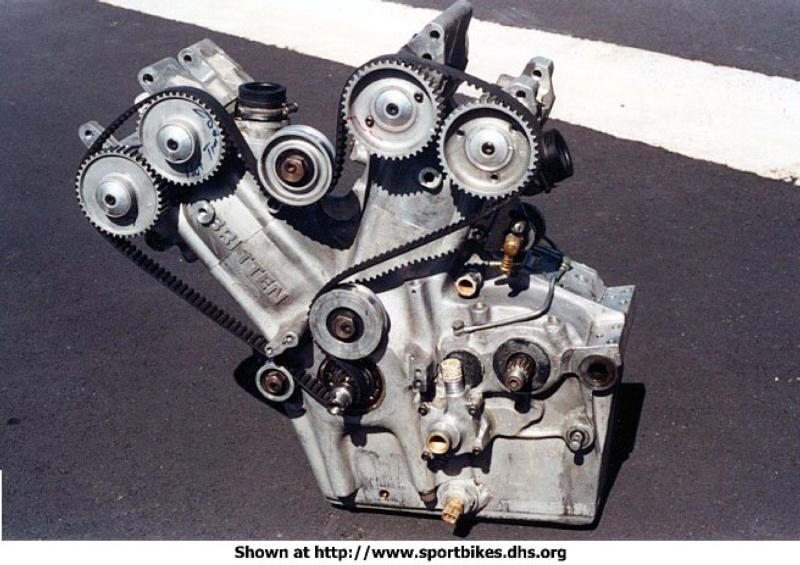

Homemade specials are usually the amalgam of the bodywork, frame, parts of the chassis, while the engine is usually sourced from existing motorcycles. But since Britten was frustrated by commercially produced engines and the lack of parts, the V1000’s engine would likewise be built from scratch.

Parts of the engine were hand cast and heat treated in Britten’s wife’s pottery kiln. There was a video of Britten extracting the oil sump from the kiln, then pouring water on it from plastic pails to cool it down. Some of the water came from the swimming pool.

The four-stroke, 8-valve, 60-degree, 999cc, V-Twin engine made 165bhp. Its ECU was programmable and also featured data-acquisition. Two versions of the engine were produced, one at 1000cc and another at 1100cc, as different race events allow different capacity caps. But most were 1000cc machines.

The innovations didn’t stop there. Everything on the bike conformed to the “design follows function” principle.

Britten didn’t like the way suspension systems of the day performed so he built the Hossack-style double wishbone front suspension system. The girders were attached to an Öhlins shock via linkages that allowed the rake and trail to be easily altered. This set up also isolated the front suspension from using up a good part of its travel during hard braking.

The large Öhlins shock behind the front wheel was in fact for the rear suspension, attached to the swingarm with linkages. Britten did so to isolate it from the rear exhaust’s heat which degrades a shock’s performance. Besides that, it made adjusting the shock much easier, compared to shoving hands and tools into a tiny space.

Speaking of the exhaust, those blue coloured, intestine-like exhaust downtubes took that form to achieve equal pipe lengths.

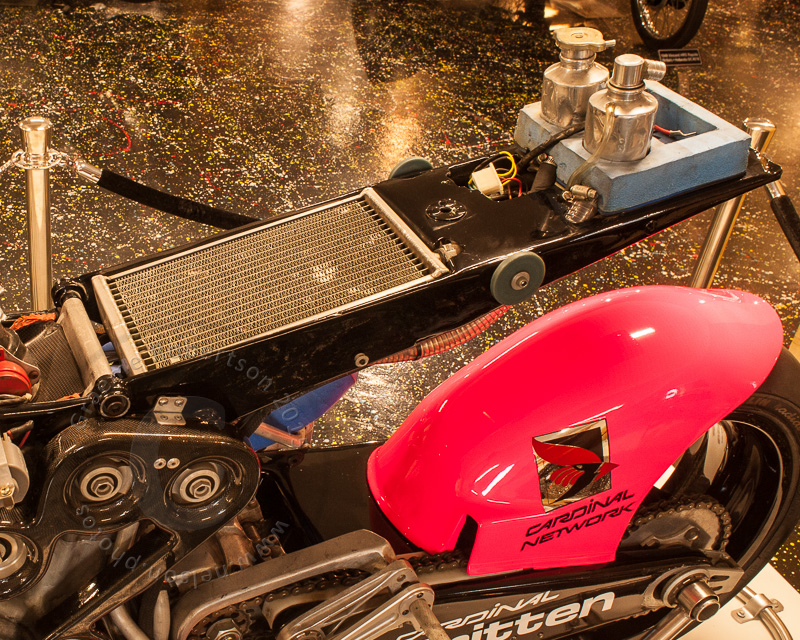

The radiator was mounted under the rider’s seat and intakes in the front of the fairing brought cooling air to it. It was done so to bring the front wheel closer to the engine to centralize mass and keep a short wheelbase, way before the major manufacturers had did anything about it.

The V1000 was essentially “frameless.” The front end and swingarm were connected directly to the engine, which was then connected to the tank as a fully stressed member, somewhat reminiscent of the groundbreaking Vincent Black Shadow/Black Lightning and the Kawaski KR500 GP racer. But those tanks were steel, unlike the V1000’s. The V1000’s frameless carbon fibre concept was later seen in the Ducati Desmosedici GP9 in 2009, followed by the Ducati 1199 Panigale in 2011.

The V1000 weighed in at 138 kg (that’s just 4 kg more than the KTM 200 Duke), and with 165 bhp, that equaled a magnificent power-to-weight ratio of 1.19 bhp/kg. Yes, current MotoGP racers and even some streetbikes do better than that but again, this was in 1991.

If these concepts were already mind-blowing to say the least, there’s probably no superlative to describe it as the V1000 was entirely home- and handmade.

But so what, if the concepts didn’t work right? The Britten V-1000 became a legend due to its performance on the racetrack.

The most lasting impression in most people’s minds was the V1000 pulling a wheelie while passing the factory Ducati at the 1992 Daytona Supertwins race, propelling rider Andrew Stroud into the lead. The V1000 led until the penultimate lap when it stopped due to a faulty rectifier – ironically sourced from a Ducati. (One of the cylinder liners had also cracked on the previous day. Another part not built by Britten.) But the V1000 had cemented its place in history, having run up front in its maiden race. It was the indisputable proof that John Britten’s concept was viable!

The V1000 went on to dominate in 1993 and 1994, winning multiple races and the New Zealand National Championship and the British European and American Race Series (BEARS). Britten and team had developed the bike along the way and it won the 1995 BEARS Championship in commanding fashion by finishing 43 seconds ahead of its closest competitor.

Britten had tested the V1000 against the FIM World Speed Records in the 1000cc and under category, too. The bike broke the flying mile record at 302.705 km/h, the standing mile at 134.617 km/h, the standing mile start at 213.512 km/h, and standing start kilometer at 186.245 km/h. It was the fastest motorcycle in its class!

It may sound like a scary bike to ride but eminent motojournalists Alan Cathcart and Nick Ienatch, among the lucky few to have ridden the V1000 reported it to be smooth and easy to go fast on.

There was no doubt the V1000 would have gone further but it was not to be. John Britten was diagnosed with inoperable malignant melanoma (aggressive skin cancer) in 1995. He passed away on 5th September that same year, at the age of 45.

There were only ten Britten V1000 ever built, in addition to the one prototype.