Carbon brakes are only used in the top echelons of motorcycle (MotoGP) and automobile racing (Formula One).

But why do only MotoGP bikes use them?

In the beginning

Braking duties began with drum brakes, which gave way to disc brake systems. But these had several limitations including overheating because they are enclosed (despite the efforts of having air inlets), and needed to be adjusted manually as the pads wear. Also, the swingarm’s movements drag the actuation arm along with it i.e. applies the brakes when the rear compresses, and unloads when the rear jacks up.

MV Agusta was the first manufacturer to fit disc brakes to their bikes in 1965, albeit on a small scale, but it was the Honda CB750 in 1969 which popularized the disc brake for road bikes.

The disc brake offers many advantages as is self-adjusting as the pads and disc wear down, it does not influence the movements of the swingarm; it is self-cooling as the disc(s), caliper(s), and pads are exposed to air flow.

Consequently, brake makers started making them more and more powerful by upgrading the master pump, calipers, discs, and pads. The calipers started from containing a single piston, to two pistons, increasing to four, and even six at one point in time.

As power increased, riders discovered they could brake harder and harder. Likewise, motorcycle manufacturers introduced bikes that went faster and faster. The more aggressive braking did not give the disc enough opportunity to cool sufficiently, especially at the track. This resulted in the disc being warped like a dinner plate i.e. the braking track began to turn outside or inside away from the carrier. When this happens, the pads couldn’t bed themselves completely onto the braking track (where the pads contact the disc). For the rider, the brake lever kept coming backwards towards the handlebar. The disc warp may not be seen with the naked eye, but the effect is there.

Brake manufacturers overcame this by producing better materials for the discs and pads to promote faster cooling. However, bikes continued to get faster and faster, so once again braking power increased and riders braked even later and harder. The lever started coming back to the bar again!

How’s that for a solution creating another problem?

The beginning of carbon brakes

The answer came from the aviation sector. As aircraft grew larger and heavier, they had to land at higher speeds otherwise they would stall. They thus needing more braking power to stop them when they touched down.

Then there was the supersonic Concorde airliner: Its delta wings required higher landing speeds. The kind of forces needed to stop the plane would melt conventional steel brakes.

Hence, Dunlop developed the first carbon-reinforced brake discs and pads in 1969.

Use in competition

Formula One cars were also getting faster and faster, especially after Lotus engineer Colin Chapman discovered the benefits of aerofoils and fitted to the Lotus 49 in 1968. From then on, the cars gained more and more downforce – grip, in other words. Consequently, drivers soon found they were stomping their brake pedals all the way down!

Brabham decided to seek out Dunlop who had developed the brakes for the Concorde, resulting in the first Formula One car to be fitted with carbon brakes in 1976.

As for motorcycles, Wayne Rainey tried them on at the 1988 British GP and was impressed by their performance and went on to win the race. Carbon brakes was here to stay in the 500cc Grand Prix class.

Benefits of carbon brakes

Carbon brakes need heat to work, in other words, heat needs to be generated and stored in the discs for the system to work at its optimum level.

This is in direct opposite to steel or iron discs, which needs to cool down, otherwise continuous heat would soon warp them or even push them into the melting point.

The first carbon brakes needed the riders to apply some pressure on the front brake lever in the first few laps to keep the discs hot. But further research and development has resulted in the materials of today.

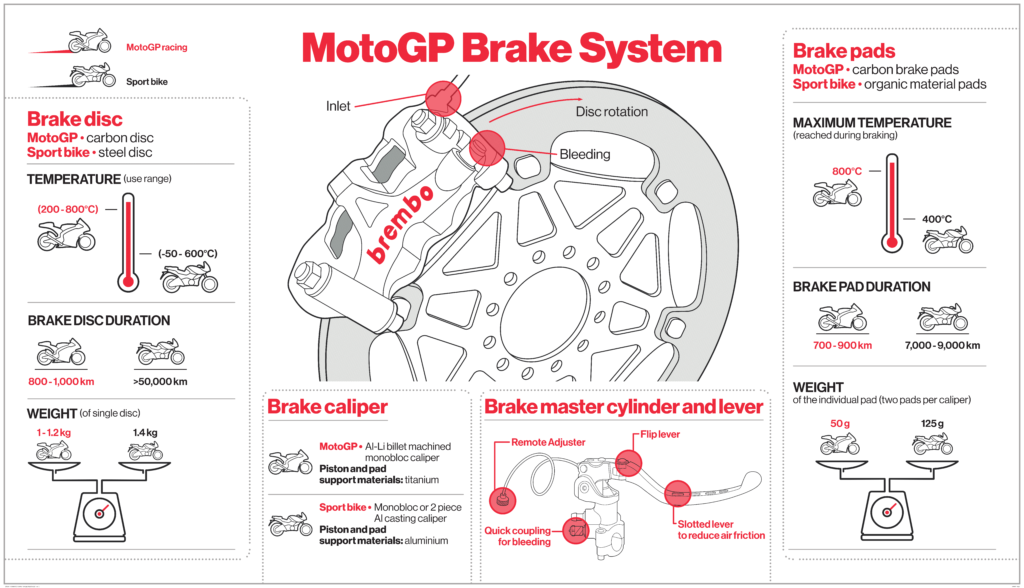

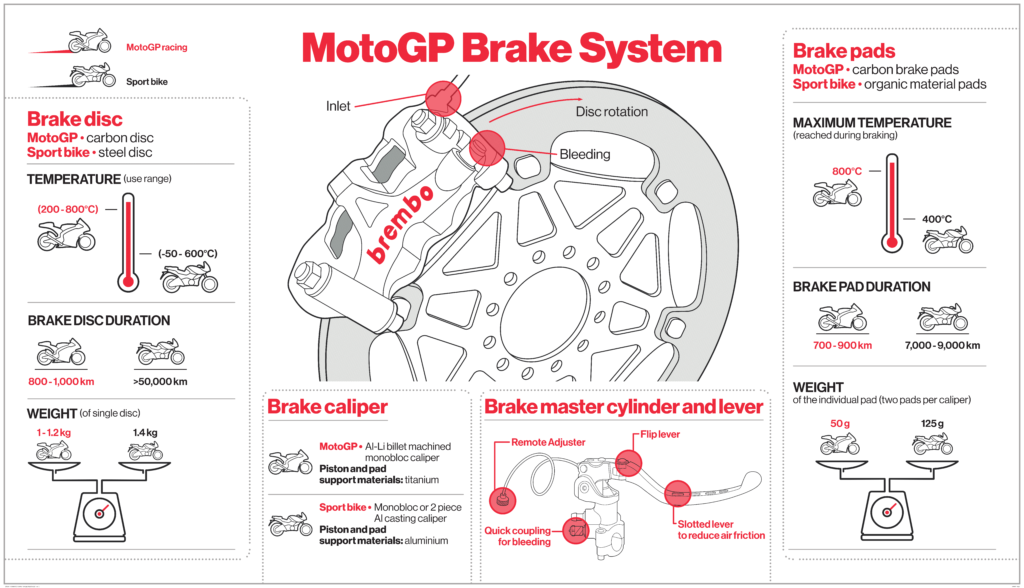

The latest system doesn’t require the rider to keep holding on to the bar to warm the brakes up. Instead, the riders only have to perform some hard braking during the Warm Up Lap. The discs will reach their operating temperature of 200 deg Celsius by the start of the race and would continue to work when kept between 200 deg to 800 deg Celsius.

But because they need heat to work, teams would swap them out for the venerable steel discs and sintered pads when racing in the rain. However, this changed when Bradley Smith finished in second place at the San Marino Grand Prix in 2015 with carbon discs and pads despite the rain. Still, it was due to the nature of the track which calls for heavy braking that manages to build up the required heat, whereas certain other tracks do not call for crazy braking.

The new brakes have much higher friction coefficiency and are so powerful that they could slow a bike from 355 km/h down to 90 km/h in less than 300 metres, in less than 5 seconds.

Another benefit of using carbon brakes is the lower unsprung weight hence reduced gyroscopic forces.

So, no wonder they cost USD 20,000 each!

But why aren’t they used in other classes?

Cost, hence the organiser Dorna and FIM decided that is would be best to mandate steel brakes for the other classes to encourage more participation. This is why carbon brakes are used only in MotoGP, while steel is the material in Moto2, Moto3, World Superbike and so forth. They were used in the 250cc class at one time but the Moto2 class has since reverted to steel brakes.

Can I use them on the streets (if one could afford them)?

No, it is too impractical for road use. There will be no way one could keep build up and hold the operating temperature in the discs in dry weather, what more when it rains and during the colder months. The only way to generate enough heat and retain it would be to keep the brake lever pressed at all times. On the other hand, steel brakes on road bikes work between -50 to 600 deg Celsius.

Besides that, the carbon discs last for only about 1000 kilometres.

The current carbon brake systems are all supplied by Brembo who had invested heavily into the technology.