Synthetic engine oil is the way to go these days as they provide the best possible protection for your engine. Being synthetic as in ‘synthesised,’ means they do not have less or even none of the shortcomings while sharing the best features of the best petroleum-based i.e. mineral engine oils.

But where did it all begin? What was the impetus that drove engine oil manufacturers to create this kind of oil?

The basics – how is lubricating oil made?

Let us refresh.

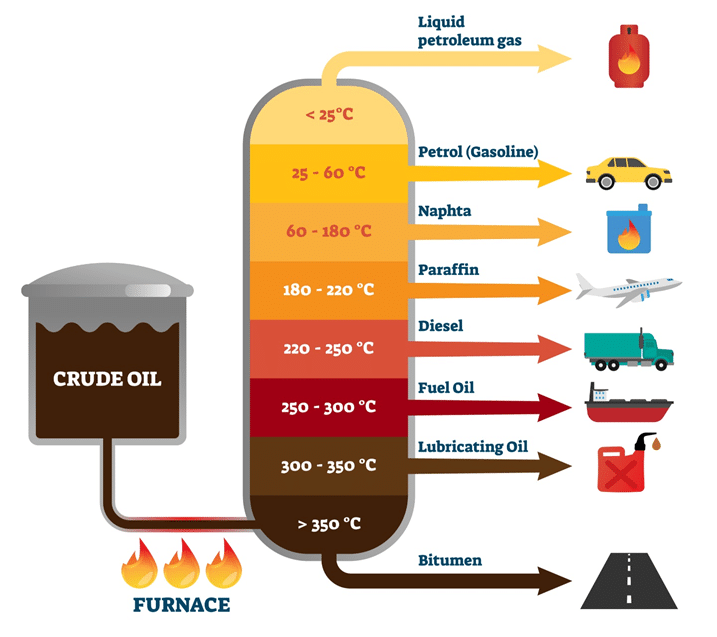

The earliest and most basic engine oils until today is petroleum based. It starts with raw petroleum (crude) drawn from the ground. This crude, which contains many different substances such as sulfur, various heavy metals (no, none are called Metallica), nitrogen, oxygen, waxes, etc., is then refined through distillation. Heat and pressure is applied to the crude in a fractional tower, resulting in the crude breaking i.e. fractioning into different groups of petroleum based groups, hence ‘fractioning.’

The ‘lighter’ (more volatile) groups rise to the top of the tower such gases, kerosene, and gasoline. Medium weight molecules become the base for lubricants, and the heavier molecules such as tar pool at the bottom.

However, distillation does not remove impurities entirely. There will be waxes and even some sulfur in the base oil, and these will soon rear their ugly sides.

Early synthetic motor oil research

French chemist Charles Friedel and his American collaborator, James Mason Crafts, first produced synthetic hydrocarbon oils in 1877.

In 1913, German scientist Friedrich Bergius developed a hydrogenation process for producing synthetic oil from coal dust.

Forward to 1925, his countrymen, Franz Fisher and Hans Tropsch, developed a process for converting a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen into liquid hydrocarbons.

Over in America, the Standard Oil Company of Indiana tried to commercialise synthetic oil in 1929, but found lack of demand. However, the company’s researcher F.W. Sullivan published a paper in 1931 that disclosed a process for the polymerisation of olefins to form liquid products.

At about the same time, German chemist Hermann Zorn independently discovered the same process. Their discoveries laid the groundwork for the eventual widespread use of synthetic oil.

End of Part 1

As we said earlier, mineral engine oil began to show its weakness especially during the Second World War. We shall elaborate on this further in Part 2.

We shall also cover the basics on how the synthetic engine oil is made is Part 2, so stay tuned.