The Yamaha NMAX “Turbo” was recently launched in Indonesia, and the name “Turbo” drew plenty of enquiries which pointed to some confusion. So, let us take a look at how turbo works.

Anyhow, the NMAX “Turbo” does not use a real turbocharger. Instead, it is a mode to switch the CVT into delivering instant torque for speeding up and overtaking.

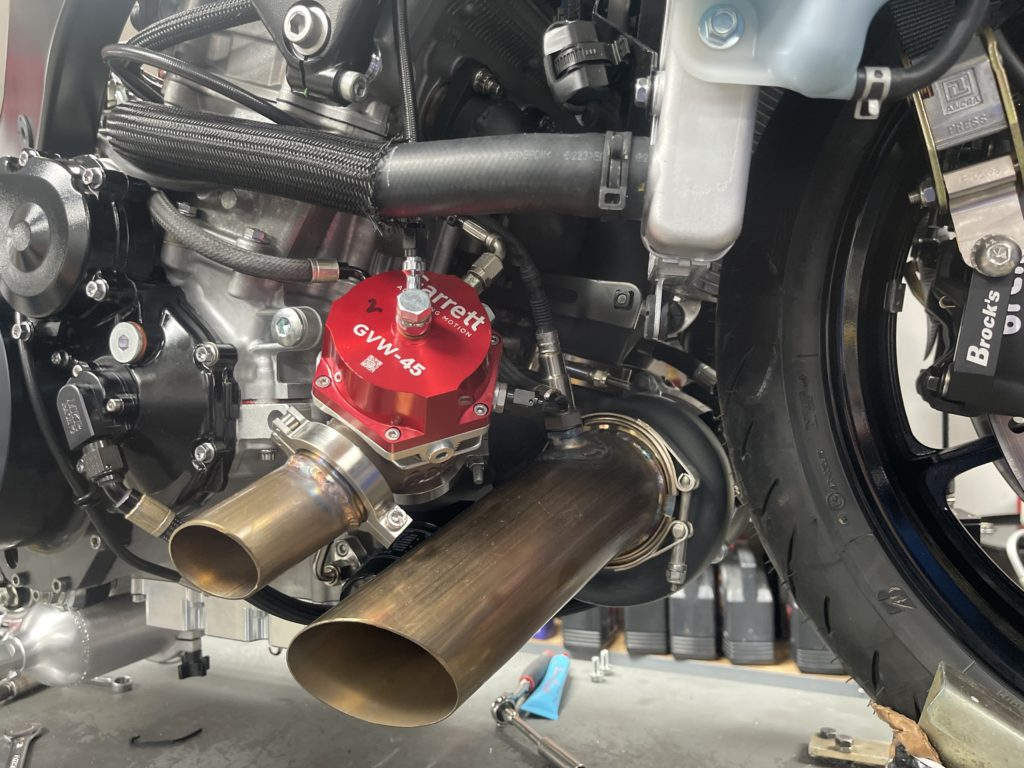

There are several reasons why a turbocharger is not popular among motorcycles, although there was an era of turbocharged motorcycles.

What is a turbo?

An internal combustion engine requires air in order to work. Air is drawn in, mixed with fuel and combusted. This combustion changes the chemical energy in fuel to thermal energy (heat), which in turn pushes the piston down to rotate the crankshaft (kinetic energy).

However, each piston can pull in so much air. Not enough air means you cannot mix in too much fuel, otherwise the unburned fuel is wasted. So, since there is not enough air and fuel, the engine produces limited torque and power.

The turbo changes this by stuffing in more air, to be mixed with more fuel, so the engine can produce more power.

How does it work?

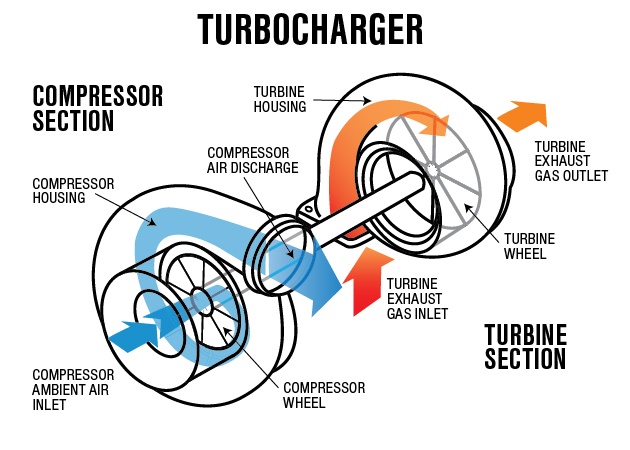

The basic premise is the turbocharger utilises exhaust gas to compress intake air, rather than letting it go to waste.

To be a little more specific, a compressor in the turbocharger pressurises the intake air before it enters the inlet manifold. In the case of a turbocharger, the compressor is powered by the kinetic energy of the engine’s exhaust gases, which is extracted by the turbocharger’s turbine.

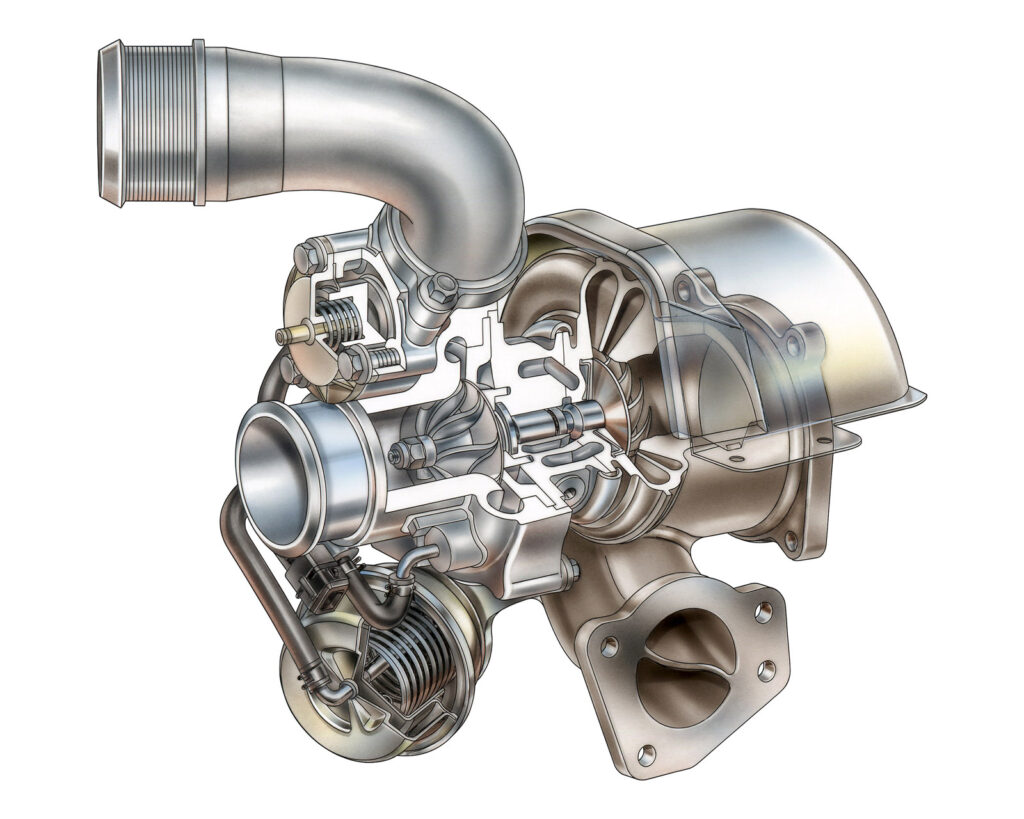

The main components of the turbocharger are:

- Turbine – usually a radial turbine design.

- Compressor – usually a centrifugal compressor.

- Centre housing hub rotating assembly.

- Turbine

The turbine section (also called the “hot side” or “exhaust side” of the turbo) is where the rotational force is produced, in order to power the compressor (via a rotating shaft through the centre of a turbo). After the exhaust has spun the turbine it continues into the exhaust and out of the vehicle.

The turbine uses a series of blades to convert kinetic energy from the flow of exhaust gases to mechanical energy of a rotating shaft (which is used to power the compressor section). The turbine housings direct the gas flow through the turbine section, and the turbine itself can spin at speeds of up to 250,000 rpm.

- Compressor

The compressor draws in outside air through the engine’s intake system, pressurises it, then feeds it into the combustion chambers (via the inlet manifold). The compressor section of the turbocharger consists of an impeller, a diffuser, and a volute housing.

- Centre hub rotating assembly

The centre hub rotating assembly (CHRA) houses the shaft that connects the turbine to the compressor. A lighter shaft can help reduce turbo lag. The CHRA also contains a bearing to allow this shaft to rotate at high speeds with minimal friction.

Some CHRAs are water-cooled and have pipes for the engine’s coolant to flow through. One reason for water cooling is to protect the turbocharger’s lubricating oil from overheating.

The cons of a turbocharger

Every engineering solution creates another problem, so it is all a compromise. The same goes for the turbocharger, hence its limited use.

Turbo lag

Turbo lag refers to the delay that occurs between pressing the throttle and the turbocharger spooling up to provide boost pressure. This delay is due to the increasing exhaust gas flow (after the throttle is suddenly opened) taking time to spin up the turbine to speeds where boost is produced (due to the turbine’s inertia). The effect of turbo lag is reduced throttle response, in the form of a delay in the power delivery.

Then, when the boost pressure is sufficient, the engine’s torque suddenly increases and the vehicle takes off, sometimes surprising the operator.

There are ways around this lag, of course, but it requires a lot of tech (read: expensive).

Heat

Needless to say the system generates lots of heat, necessitating the use of oils that could stand up to the torture. Hence, only synthetic engine oils are recommended.